History

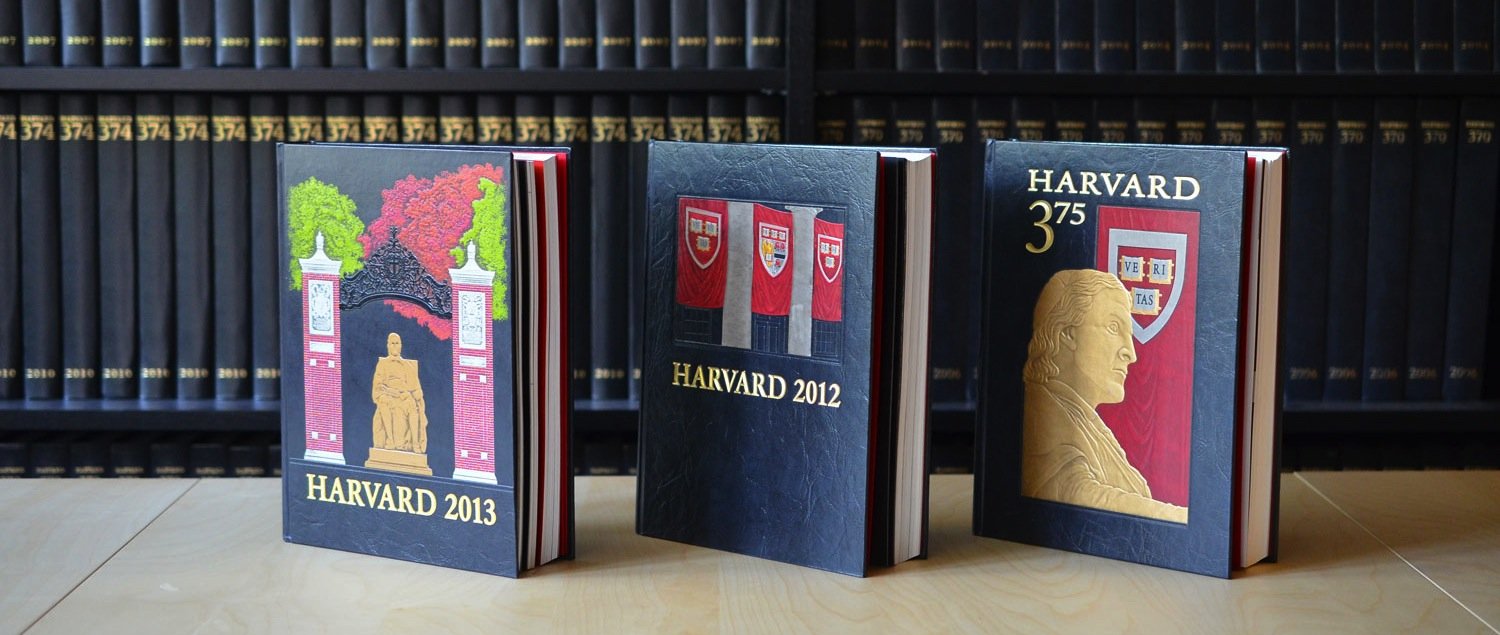

60+ years of Harvard Yearbook.

(Excerpt from a letter by the Editor-in-Chief of Harvard-Radliffe 353.)

Amazing things can happen when one reads. One can actually learn something interesting. Late one Saturday in January, when I should have been working on law school applications, or at least an overdue economics paper, I was once again in the Yearbook office flipping through old yearbooks. The 1968 book happened to have a few eye-catching photographs and I decided to glance through the rest of the book. Finding the pages with the article describing the Yearbook (which we yearbook types always look for), I noticed a mention that the first Harvard Yearbook was called the Harvard Portfolio and published for the 1889-1890 school year. What?

The Portfolio lasted until superseded by the publication of the Harvard Album in 1898 which continued through 1949. In 1949, a group of students dissatisfied with the blandness of the Class Album (the Harvard Album had been renamed some time earlier) founded Harvard Yearbook Publications and published 314 in 1950. A little arithmetic will show that this is the 40th volume produced by Harvard Yearbook Publications, but more significantly this is the 100th Harvard yearbook. One hundred. But no fanfare, no special section devoted to "100 Year(book)s at Harvard," no corny comparisons between students now and students a century ago. In retrospect, it is probably best that I discovered this book's significance so late because, given time, I might have been inclined to do something extremely trite. The basic fact is that by January the yearbook was 60% complete and tightly structured for the remaining 40%. The only adequate space to tell my little story was within the Editor's Note.

It is pretty unusual that an organization would not realize how old it is -- especially one whose primary function is to preserve history. However, our records are not particularly good and many things have been lost over the years. It's just a bunch of kids working hard wherever we can find space year after year. Nobody bought us a Castle. We don't have a building on Plympton Street. We started out in the Student Activities Center and from 1955 until 1981 we were at 52 Dunster Street until ousted by the University in favor of the Office for Career Services. We moved to the basement of Grays. We were in the basement of North House before we discovered some asbestos in the walls which might lead to a few problems. We were in Memorial Hall until we got tossed out to give Harvard Real Estate more space. Now we pay for an office and a darkroom, neither of which has ventilation, in the basement of Cabot Hall. Nobody ever said the Yearbook was a place for stable people. At times we seem to change our office as often as we change our title. I don't think one has to ask why our mailing address is a post office box. So the adventure continues.

The Advocate has had T.S. Eliot, Theodore Roosevelt, and Norman Mailer. The Crimson has had FDR, JFK, Caspar Weinberger, etc. The Lampoon has had John Updike and even Elmer the Custodian. Past Presidents and Editors of the Yearbook include names such as George Feeney, Edward Kenyon, Roxane Harvey, Lee Smith, and Ken Meister -- significant in their own right but not particularly etched in Harvard lore. Still, we no-names do indeed have a lore of our own. Especially after the Class Album and the Freshman Red Book were replaced by 314 and the Freshman Register, this student-run publication has had its moments. The Freshman Register produced in the mid- to late 1950's was somewhat different from today's editions. Of course the Register contained the usual mug shots and pre-college information but, when the young Harvard men were tired of looking at themselves, the last few pages provided drink recipes (including "Purple Passion," "Rebel Mountain Dew," and "Artillery Punch") and descriptions of women's colleges in the Northeast -- with the appropriate phone extensions. A "business trip" by two Yearbook staffers yielded this observation of Smith College: "...girl after girl is again almost monotonously attractive. We also find that they are friendly and even sometimes intelligent." They were more impressed by Vassar: "...the finest, the absolute finest...ah Joy!: Vassar, thou exemplar of all that is fine in college women!"

Also in the late 1950's we started calling ourselves the Aardvarks when we experienced a dispute with the Crimson. The Crimson had continually neglected to place our ads in the newspaper. The excuse was that ads were inserted alphabetically; by the time they got to the Yearbook ads, space was invariably exhausted. Solution: call ourselves the Aardvarks. The 1960's witnessed how ambitious the Aardvarks could be: at various overlapping points we published a magazine called Cambridge 38, the Harvard Handbook, the Harvard Freshman Register, the Radcliffe Register, the Radcliffe Yearbook, and, of course, the Harvard Yearbook. Inclusiveness in the College was reflected in the Yearbook as well. In 1965 the Harvard and Radcliffe classes were finally joined within a single Yearbook; the 1969 book devoted 24 pages of essays and photos to the recently expanded Black community at Harvard.

We haven't been exempt from controversy either -- a couple of Yearbooks in the early 1970s were full of normally taboo words and contained photographs of nude men and women. Equally notable is something we almost didn't publish -- the Class of 1985 Freshman Register -- to protest our lack of adequate office space. At least we've been interesting even if we haven't produced a litany of famous ex-members.

Maybe our staffers don't seek notoriety as a validation of their work. Maybe we like it that way. People who join our staff are not looking for great pressure nor intense competition. But exactly why they do comp the Yearbook is not definite. It's not for the free T-shirt nor the free food (although it could be the free wine coolers). Perhaps the paraphrasing of a few statements from 337 says it best: it is a lively business with just enough crises to keep the staff coming back for more; not as prestigious as the Crimson, as socially useful as Phillips Brooks House, as funny as the Lampoon, as news-worthy as the hockey team, nor as controversial as the faculty, but somehow trying to capture a little of all these things and more...

Still, every year, capturing "these things" means something different for the Editors. As stated in the "Prologue," this Yearbook does not purport to be the definitive encapsulement of undergraduate life at Harvard and Radcliffe. What we have tried to do is cover many of the specific elements of the Colleges which are representative enough to convey an understanding of the whole...

I guess it can be said that yearbook staffs tend to be a fairly self-congratulatory lot. We listed the executive board on page 2 and splattered our faces throughout the book. Two pages are taken up by the staff names and photo credits. Then the Editor takes two more pages to thank them for doing it. We think what we do is important and perhaps we thank ourselves because we don't hear it from anyone else. It's in the timing of the Yearbook's arrival that soon afterwards underclassmen go home and seniors go into the real world. The business board may get thanked while they're distributing the books, but when the production boards return in the fall, no one comes over to say "thank you." We understand.

There is an implicit thanks when the books are bought and our account contains enough money to continue publishing for at least one more year. We know that we haven't made The Perfect Yearbook, and by 2089 there still might not be one. Nevertheless we are ambitious and we won't stop trying. The fact that we are given the privilege to attempt to get just a little bit better next time is thanks enough for our efforts. And my own experience lets me feel comfortable saying, on behalf of one hundred great years of Yearbook staffers, that you are very welcome.

Michael O. Whitmire

Editor-in-Chief, Harvard-Radcliffe 353